“Redknap’s men would wend their way through the Poplar marshes, and would need more than a pint of Ale when they arrived at the Inn on Dolphin Lane, they would be looking out for a meeting with Edward Dyer a fellow Waterman from the lane, to row their packages across to the Wealthy residents of Greenwich and upriver to the City of London.”

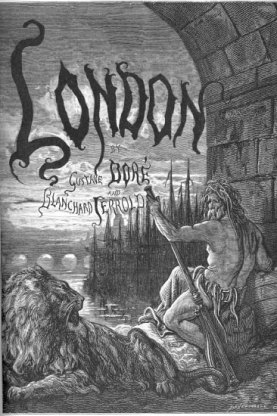

Father Thames

The Thames was t he main thoroughfare of London, its name goes back to pre-Celtic Indo-European languages as Temisios, to the Romanised version as Tamesis, the name just meant dark or muddy river. The river kept its name as Tameis until the 16th century, when an “H” was added in order to try to reinforce the false idea that the name was derived from Greek and Celtic. The many foreign sailors who plied the river called it “The London River”, but to Cockneys, to this day, it is just “The River”, everyone in London knows which one you mean.

he main thoroughfare of London, its name goes back to pre-Celtic Indo-European languages as Temisios, to the Romanised version as Tamesis, the name just meant dark or muddy river. The river kept its name as Tameis until the 16th century, when an “H” was added in order to try to reinforce the false idea that the name was derived from Greek and Celtic. The many foreign sailors who plied the river called it “The London River”, but to Cockneys, to this day, it is just “The River”, everyone in London knows which one you mean.

The River has two different physical parts; the tidal part reaching from the North Sea and English Channel to Staines, which meant that the level rose and fell up to 28ft at some points, and indeed The River could be seen to flow in both directions, both upstream and downstream depending on the direction of the tide, lending the river a strange and mystical air to the natives who settled on its banks; a river that flows backwards at certain times of the day was indeed a strange thing. On this tidal stretch the river rarely flooded more than the marshes on its banks, but could summon up a terrible flood when influenced by tidal surges from the North sea. The tidal river brought the wealth of the world’s nations to London in commercial trade, plus more domestically, the Coal and Timber of the North of England, the Limestone of Southwest England, as well as the fruit and veg of the market gardens of Kent and Essex. The other half of The River, the non-tidal part, flowed from its source in Gloucestershire down to Staines; faster flowing, fed by the rain off the fields and hills, and tending to break its banks to feed the fields that grew the corn and cattle to help feed London.

In these ways The Thames extended London’s reach from Gloucestershire to the North Sea along its navigable length of over 230 miles. However, as well as the division between Tidal and non-tidal Thames, there was a much more local division to London. As already mentioned in Part 1 of Danny Dyer’s Family History, London Bridge, built on a shallower part of The River, stopped the travel of larger vessels upstream. This meant that to get upstream through the dangerous arches under London Bridge took great skill and experience, unskilled boats were frequently capsized trying to shoot the arches of London Bridge, and many passengers were drowned and goods lost. In an age of poor roads, in a crowded City, where the easiest and fastest transport was by boat, the need for skilled and trusted boatmen was high.

Watermen and Lightermen

It is into this environment in the boom time of the British Empire, that Edward Dyer (Danny Dyer’s Great Great Great Great Grandfather) enters the story and takes his apprenticeship as a Waterman in 1803 at the age of 14. This meant seven years of  indentured labour. In return for being clothed, housed, feed while he learned his trade, Edward would agree to work six days per week for his Master, wouldn’t swear, gamble, or take strong liquor, and absolutely could not marry during that time, he may have received no wages at all, or perhaps the odd piece of pocket money, a hard life for a boy, but at the end of it he would be a man with a profession, licensed to carry passengers and goods safely on the Thames. He would also have developed a physique to match his work’s demands, pulling on big oars in a Thames Wherry up, down, and across the river, six days per week, several hours per day, would build a magnificent physique, a strong back, big arms and shoulders, and calloused hands with a vice like grip, plus the stamina of a cart horse.

indentured labour. In return for being clothed, housed, feed while he learned his trade, Edward would agree to work six days per week for his Master, wouldn’t swear, gamble, or take strong liquor, and absolutely could not marry during that time, he may have received no wages at all, or perhaps the odd piece of pocket money, a hard life for a boy, but at the end of it he would be a man with a profession, licensed to carry passengers and goods safely on the Thames. He would also have developed a physique to match his work’s demands, pulling on big oars in a Thames Wherry up, down, and across the river, six days per week, several hours per day, would build a magnificent physique, a strong back, big arms and shoulders, and calloused hands with a vice like grip, plus the stamina of a cart horse.

Romantic Deptford

During his time plying passengers between the North and South Banks of the Thames, Edward met Mary Robertson from Deptford on the Kent (South) side of the River, he was no doubt courting her between trips to and fro from the old East India shipyards at Deptford, to the new East India Shipyards at Blackwall, and, immediately after he finished his apprenticeship and was free to do so, he wasted no time in marrying Mary on 28th June 1810 in St Alphege Church at Greenwich.

Ironically St Alfege was the Archbishop of Canterbury who was unlucky enough to  have been captured by the same Danish Vikings who had captured London, and been seen off from by the Norwegian Viking Olaf (St Olave in Part 1 of Danny Dyer’s story) when London Bridge was pulled down. Alfege really was unlucky, his monks were unable to raise the ransom asked by the Danes for his release, so the Danes took him down near The River and executed him, on that spot was built St Alphege’s Church, and rebuilt in 1712-1714, this is where Edward Dyer and Mary Robertson married.

have been captured by the same Danish Vikings who had captured London, and been seen off from by the Norwegian Viking Olaf (St Olave in Part 1 of Danny Dyer’s story) when London Bridge was pulled down. Alfege really was unlucky, his monks were unable to raise the ransom asked by the Danes for his release, so the Danes took him down near The River and executed him, on that spot was built St Alphege’s Church, and rebuilt in 1712-1714, this is where Edward Dyer and Mary Robertson married.

The couple set up home in Butcher Lane Deptford, where their first child Elenor Dyer was born in 1812. The sojourn South of The River was short lived, and by 1814 when their second child, named Edward after his father , is born in Limehouse.The couple would have six more children up to 1832 all born in Poplar.

London Bridge Really was falling down

“London Bridge 1830”. Licensed under PD-US via Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:London_Bridge_1830.jpg#mediaviewer/File:London_Bridge_1830.jpg

Times were changing, in 1810 Locks were put in up River at Teddington, bringing the tidal reach of the Thames back 16 miles down river from its former reach at Staines, taming and controlling the River’s ebb and flow upstream. A more important change for Edward Dyer the Waterman was when London Bridge finally did fall down, this happened when the “new” London Bridge was built between 1825 and 1831, the old bridge was torn down once the new bridge was completed, and the new bridge had a major impact on the Thames Watermen. Much wider spans meant that progress for boats was much safer than it had been, so people could be transported with much less risk, and this was taken advantage of by unlicensed watermen, swarming like unlicensed mini-cabs to transport travellers up and down the river. Worse still, steamboats came onto the river scene in large numbers from the 1830s and by 1835 it was estimated that around 3.5 million passengers travelled per year between The City and Blackwall, virtually all by steamboat.

Watermen would need to pick up adhoc passengers wanting private transport and any given time that it was required. This was reflected in the impact it had on Edward’s living, he temporarily went into transporting goods rather than people as a Lighterman in 1828, and the building of an Iron Bridge over the River Lea into Essex, and the roads linking Poplar from Blackwall to North Millwall, and on into the City meant that foot and horse travel was greatly improved all the way from South Essex into the City of London, with an associated decline in the need for the transport of travellers by Watermen on the river. This period also coincides with outbreaks of Cholera among dockside communities, and Edward and Mary lost three of their children in infancy between 1814 and 1831, Edward, Caroline, and Emma.

But the early 1800s weren’t all bad news for the Dyers, despite the declines in certain routes for Watermen and the tragic loss of their children, work was always there as the Docks boomed, so there was always a background demand for transport, and Mary’s family connections across the Thames in Greenwich and Deptford opened options for transporting workers across to Blackwall as the new and expanding docks drew in many workers from south as well as north of the river. And big families meant at least some children would survive.

Just as the Dyer’s Family had risen in three generations from 4 and then 6 Dyers, to Edward and Mary’s Family of 11 children and adults, albeit reduced by the Cholera Father Thames brought to their door, Poplar had also grown from 1,000 people in the 1600s to over 4,000 in 1801, and tripled again to more than 12,000 by 1821.

An echo of Smugglers

The Dyers lived in Alpha Street. Alpha Street had an interesting history, as it developed from the old Poplar marshland path which ended in the local Beer House and a few cottages, a welcome sight for any lost travellers that had wandered through the marshes of pre-industrial Poplar. This sounds innocuous, but the sight of the tavern and the Watermen’s cottages appearing out of the mists of the Poplar marshes would also have been a welcome sight to men travelling with carts and pack horses filled with luxury goods, which may have avoided Customs Tax on its way over from France and the Netherlands.

Goods were brought to landing places at Blackwall and the River Lea by the (alleged) smuggling Foreman family (ancestors of Jamie and Freddie Foreman of acting and Kray Twins fame) bringing goods upriver from their Boat Yards at Faversham, a handy route avoiding the Royal Naval Cutters on the Isle of Sheppey. Enos Redknap (ancestor of Harry and Jamie Redknapp of footballing fame) Landlord of The Gunn Inn at Cold Harbour would be a man to deal with, under the patronage of the Royal naval Boatyard close by, the sailors turning  “Nelson’s Eye” to the unofficial business ventures of this man from a long line of King’s watermen. Redknap’s men would wend their way through the Poplar marshes, and would need more than a pint of Ale when they arrived at the Inn on Dolphin Lane, they would be looking out for a meeting with Edward Dyer a fellow Waterman from the lane, to row their packages across to the Wealthy residents of Greenwich and upriver to the City of London.

“Nelson’s Eye” to the unofficial business ventures of this man from a long line of King’s watermen. Redknap’s men would wend their way through the Poplar marshes, and would need more than a pint of Ale when they arrived at the Inn on Dolphin Lane, they would be looking out for a meeting with Edward Dyer a fellow Waterman from the lane, to row their packages across to the Wealthy residents of Greenwich and upriver to the City of London.

The Taming of the Marshes

As the marshes in North Millwall were dug out to build the docks for the East India Company, Alpha road developed a position as a route between the Millwall and West India Docks. The days of smugglers were coming to an end, to be replaced by the Dockers and shipwrights. The older cottages from the 1700s penetrated by the cold and damp miasmas of the marshes, a harsh environment to try to raise nine children in, both the floors of houses and the marshland paths were dirt based, but by the early 1800s these were starting to be replaced by houses thrown up by speculators which were still rough and slum like, but set out in straight lines with wooden floors along cobbled streets.

Times were changing, some things for the better some for the worse, Edward and Mary’s surviving daughters would marry local Smiths, Boiler Makers, and Shipwrights, and their one remaining son Edward William Dyer (Danny Dyer’s Great Great Great Grandfather) would serve as an apprentice to his father as a Waterman, and his Father Edward would persist in his trade as a Waterman, but the takings were ever diminishing, and in Edward’s case would lead to poverty and eventual death In Poplar workhouse in 1864, Mary outlived him by a few years to 1867, moving one of her daughters and her family in and working as a Housekeeper. Both Edward and Mary Dyer had lived into their seventies, a good age for working class people in early Victorian London. But now the steamers on the Thames easily passing London Bridge and offloading their passengers onto purpose built jetties had stolen the Waterman’s Trade, the removal of trade barriers and a numerous Customs and Police Force spelled the death of smuggling, and the metal ships in the dockyards heralded a new age. We shall see in Part 3 how the Dyers adapted.

(If you would like your Family tree uncovered, it costs £600 for a full surname line, and makes for a great present. Contact me on paulmcneil@timedetectives.co.uk if interested.)

2 Replies to “Danny Dyer’s Family Tree Part 2: Watermen and Lightermen”