Having seen the real lives of Hezekiah Moscow and Alec Monroe, we now move on to Henry “Sugar” Goodson.

The Goodsons

Henry “Sugar” Goodson was the seventh child in a family of twelve children, six boys and six girls, the children were born over a period of twenty three years between 1843 and 1866 which meant that his mother Sarah spent most of her adult life either pregnant or breastfeeding. She also was forced to bury two of her youngest children, both girls, in the 1860s.

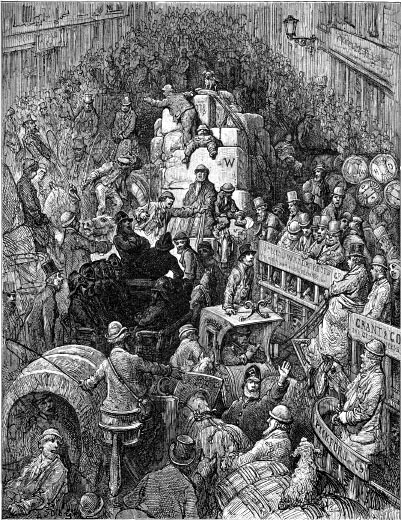

Henry (Sugar) was a Carman, from a line of Carmen, both his father and grandfather having the same trade, as did his brothers, and his mother Sarah also worked in the business once the last of the children were weened. Carmen were the haulage contractors and “White Van Men” of their day, they were the lifeblood of trade outside of ships and railways, and would move goods around tow, and further out to the home counties providing the flowing bloodstream that allowed trade to flourish in the Capital and beyond. It was all very well to get bulk goods delivered by ship to the docks, or by rail to the sidings, but who was going to get your goods moved around the streets? Who was going to deliver the small things? Well, Carmen like the Goodsons would.

The Goodsons were based in 7 Star Yard, off of Brick Lane in Spitalfields in the East End of London. Sugar’s father Edward was a “Master” Carman and Contractor, which meant that he had men in his employ, and took on jobs for other businesses and probably bid for work with local Government in the form of The Parish. This may also have been the case with Sugar’s grandfather Joseph. This employment of men meant that Sugar grew up in a successful working class background, they were running a business and making money, but would’ve been looked down upon by the Middle Classes as “Tradesmen”.

in 1833 when Sugar’s Grandfather had the business, the Goodsons were operating as “Goodson, Jones, and Davis” most likely the three carmen having come together to form a bigger company. They operated from a brick built house and five brick built stables at 7 Star Yard at a rent of £47 per year, roughly equivalent in terms income flow to £81,000 per annum in today’s money. So the Carmen had to earn a pretty good living to have been able to have afforded their annual rental.

The business went from Joseph Goodson, Sugar’s Grandfather, to Edward Saunders Goodson his father, to Sarah, Sugar’s mother when her husband died in 1877. Fortunately for Sarah her youngest child was eleven by 1877, and a working class child who had reached double figures, and had older siblings would’ve been independent enough to look after themselves, giving a Sarah a chance to keep the business going. As, although we tend to think of the Victorian era as being male dominated in business, which generally it was, women who had a strong personality sometimes turn up in the records taking on the family business when their husband died, and this isn’t the first time my research has found this in the Cabman and Carman Industry in Working Class London (the same happened to the Spandau Ballet Kemp brothers’ tree that I researched for ITV’s DNA Journey) probably because the women of the family would help look after the horses, stables, and money accounts whilst the men went out on the cars (horse drawn carts) and “vans” (enclosed horse drawn carts), which the women aren’t recorded as doing in commercial companies of the time.

With Sarah running the business she had her hands full, not helped by Henry (Sugar) keeping bad company, he had been accused of stealing a van in 1877, but had been found not guilty, and in August 1880 when on his way to a delivery in Kent, fell in with two groups of friends, and had them accompany him in his van for a summer’s day trip to Kent. When they got to Eltham in Kent a Lady had her purse stolen in a Post Office. Sugar and his companions were arrested as they travelled through the Town in the van, and the Police found various pieces of paper in the back of the van that appeared to have come from the purse. The case ended up in court, Sugar had various character witnesses brought forward, and said that he was just driving the van and knew nothing about any theft, the magistrate took him at his word and discharged him. As there were no witnesses to the offence the rest of the defendants were all eventually acquitted. Interestingly, it turned out that a number of the young men involved had extensive criminal records, including theft from the person (pick pocketing), violence, and other thefts. A year later in 1881 Sarah’s son Edward, Henry’s brother, was prosecuted by the RSPCA and convicted of working a horse in unfit condition and fined.

Hard Times

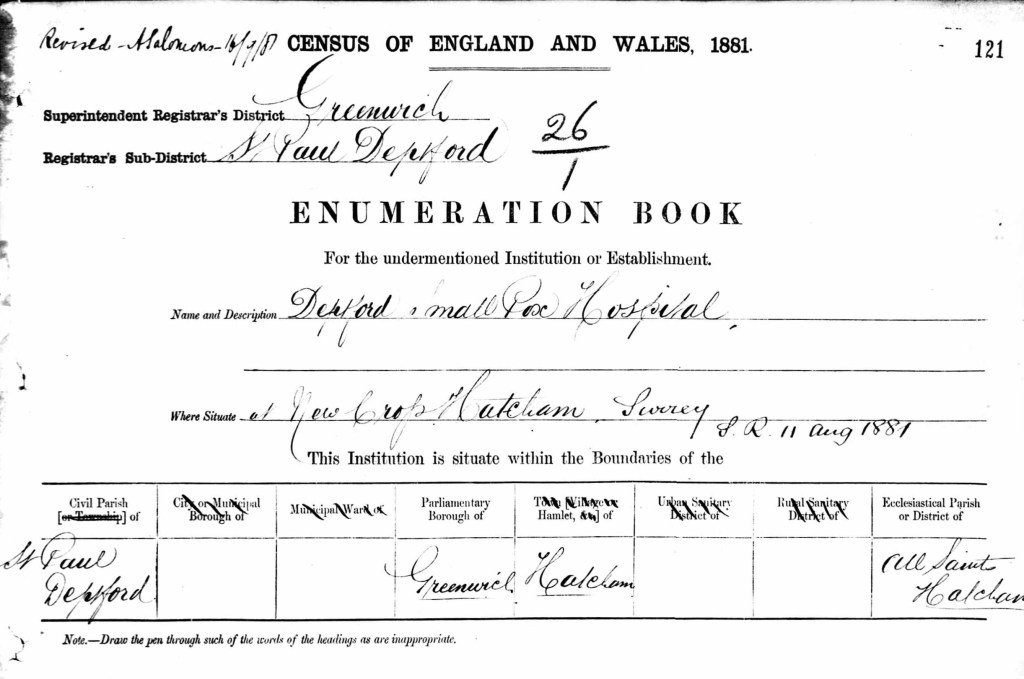

Having been running the business from 7 Star Yard for well over half a century, it fell on Sarah to be faced with hard times, there was a fire at the Yard in the late 1870s, in 1880 her son Benjamin was accused of being involved in the theft of a horse and cart from Essex but was found not guilty. In 1881 Sugar was struck down with Smallpox and admitted to the Deptford Small Pox Hospital across The River (The Thames is always referred to as “The River”) on the “Surrey Side” in what would now be South East London. As referred to by the the enumeration title page from the 1881 census below.

This institution had been built in 1877, so was state of the art for the time. Built after the wave of Smallpox outbreaks in the 1870s, and was regularly overwhelmed with admissions during the smallpox epidemics of 1881-1884, one of which Sugar fell victim to, although he did manage to gain admission, fortunately as he had a wife and three small children at home. Mortality from Smallpox was around 10% to 30% at the time, so as a fit healthy young man his odds of recovery were fairly good, and even better if properly cared for. However, one of the signature lasting symptoms of Smallpox was blindness. Up to 5% of patients became blind, and up to 20% had significant visual impairment. According to later accounts Sugar was blind or at least visually impaired in one eye, so it would seem that this probably occurred as a result of his contracting Smallpox.

The business suffered, and in December 1882 a “bill of sale” was held against Sarah for £400. A “Bill of Sale” in 1882 is not what it sounds like today. In Victorian commercial practice, a Bill of Sale was a public legal notice that a trader had assigned, mortgaged, or transferred their goods and stock-in‑trade to a creditor. It was effectively a warning to the world that the business owner no longer fully owned the goods on their premises.

Worse was to come, in 1883 Sugar’s youngest son Arthur died at a year old. In the same year Sarah’s son (Sugar’s older brother) Benjamin was found guilty of receiving stolen goods, and sent to prison for fifteen months with hard labour. As if this wasn’t enough for Sarah to deal with, again in 1883, the business was forced to pay damages to a well to do lady when one of their Vans collided with an open carriage, that threw the Lady out of the carriage injuring herself. Most of the witnesses claimed that the carriage was at fault, but the Gentlewoman won her case for damages although only just over £60 was paid instead of the £100 she claimed. Enormous sums at the time. This seemed to push the business over the edge, and Sarah took the business into voluntary Liquidation in the same year.

Divisions in the family flared up, and in August 1883 Sugar was hauled up before the Magistrate for threats against his older brother Edward, however Edward failed to appear to give evidence, and the situation was summed up by Sugar, who, upon the case being dismissed, laughed and saluted the Magistrate with the cheeky remark of “Thank you for that!”.

Whilst her sons squabbled and let her down, Sarah was busy paying off the businesses creditors with dividends from the company’s profits to keep things going.

It’s possible, that whilst his brothers knuckled down working as Carmen for their mother, Sugar attempted to generate more income by taking bigger risks for financial rewards in his boxing career, flirting with the law, on the edge of illegality, in order to help shore up the family. as we shall see, the rewards could be very good, but the risks were also there.

Boxing Career

Sugar is said to have started his boxing career in 1873 against a fighter named Bos Tarry, but the earliest public mention I could find of him fighting in the ring was 1878/79 when Sugar started his professional boxing career in London at The Old Mile End Gate Tavern, where he was billed as “Sugar” Goodson rather than Henry, boxing at 9 stone 6 pounds (137 pounds) and where he is described as Denny Harrington’s Novice. The inference was that Sugar had trained under Denny Harrington, a ferocious ring and street fighter, dock worker, and Irish immigrant. By the early 1880s the two were in contest with each other in exhibition matches at the Five Inkhorns in Shoreditch, and later at the Bluecoat Boy where Sugar and Denny would occasionally take each other on in “The Grand Wind-Up” – the the main event and finale of the night of sparring.

By 1881 Sugar and his brother Tom Goodson (sometimes referred to in modern times as “Treacle Goodson” although I can find no contemporary reference to him by this nickname) were running the boxing Saloon at the Bluecoat Boy for “Punch” Lewis. Tom Sugar and Tom would spar with other boxers and act as opposite cornermen for competing boxers, and it was here that Alec Monroe turned up to spar professionally. The the promoters increased the novelty of Alec sparring local white opponents by giving blackened gloves to Alec and whitened gloves to his opponent, so that each punch that landed left a black or white mark on the opponent’s skin. These matches were much more about novelty to generate takings than about violence, this kept them inside the law, generated a wider audience, and allowed the boxers to recover more quickly between events so more events could be put on during a year.

Interestingly Charlie Barlett (sometimes called Bartley) described as “this civil young coloured boxer better known as “The Meat Market Black” fought against “Ching Hook” – Hezekiah Moscow at The Bluecoat Boy, and Hezekiah continued to fight at the pub where he was sometimes billed as “The Black Chinaman” simply to excite interest and pull in the crowds, from which he benefited, despite the bizarre billing. Punch and the Goodsons were nothing if not inventive in their marketing of the boxers appearing. Although these Ring Names grate on our modern ears, it was not meant as derogatory at the time, merely a way of upping the interest in their fights, black people being rare in the UK at the time, and Charlie Bartlett’s background was one of living in the Smithfield Market area of “The City of London” that had seen a mini-boom in the 1860s with the renovation and updating of The City of London’s main wholesale Meat Market at Smithfield, where workers carried carcasses of pigs and cows for the butchers. This would have made Charlie popular with the hard working hard drinking market porters who would back “their local man” in the ring.

Punch Lewis, Sugar and Treacle then took to staging bouts for a Silver Cup as a prize, and put together a varied card, with as many variations on the novelty of contests as they could, for example in 1881 they had Harry Solomons “The Champion Israelite”, Denny Harrington fighting Sugar as a kind of master and pupil contending with each other, “Nimbo” and (Alec) Monroe billed as the Black Boxer, and with Sugar as MC who would also spar with “all comers” so members of the audience could try their hand against him, mostly after they’d had a few pints, and could retire for the evening with a few bruises but able to boast that they’d gone a round or two with Sugar Goodson. By this time Punch and the Goodsons were charging tuppence (two pennies) just to get in, alongside the takings from food drink and possibly gambling – illegal but should it happen clandestinely, of course without the organisers’ knowledge (at least that would be the story should the Police nose around).

Holy Orders: The Notorious Fight in the Chapel

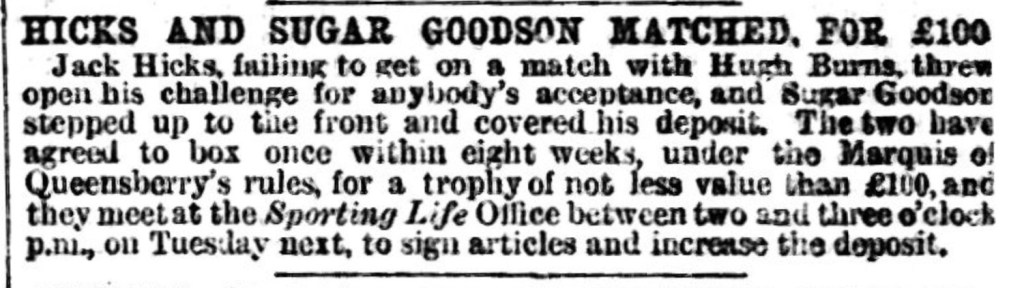

By 1882 Sugar and Tom had signed up to fight under Marquis of Queensberry Rules, mainly because this gave the bouts the air of respectability and there was huge money coming into the sport from the Middle Classes and Aristocracy for the more formalised form of the sport. Sugar took on a bout for £100 prize cup, and Tom for £50 prize money. £100 in 1882 compared to average earnings would have been the equivalent in today’s money of around £65,000.

Sugar was trained and brought to fitness at the Wakes Arms Inn Epping by his old mentor Denny Harrington, as the fight was initially planned to go ahead in Epping. Sugar was 25 years of age and relatively inexperienced in formal Queensberry bouts, but had ample experience from the rougher end of the market. Sugar sttod at 5ft 5and 3/4 inches, and weighed 11 stone (154lbs). His opponent Jack Hicks was 50 years old (!), was the same height as Sugar, but was 10 st 2 lbs (142 lbs).

Sugar was on course to win the match, but the Police decided to raid the event, forcing a premature end to the fight.

The main problem was that a crowd of some hundreds of East End Working class men and boys had turned up and were presenting a disturbing spectacle to the Constabulary who it seems had been initially prepared to give the match the benefit of the doubt, but once they claimed to have seen a few indiscretions in the ring, and the crowd inside and outside of the venue started to become more raucous, that they then decided to bring the match to an end.

When the Police intervened a general movement happened as the crowd in the Hall made a hasty move for the exits to avoid arrest, to the consternation of the Policemen present. The situation was compounded by scuffles between Police and “roughs” outside the hall after the doors were locked to non-paying customers, an element of the external crowd decided to try to force their way in by kicking at the locked doors, the Police outside intervened to arrest the worst offenders at which point a number of fist fights broke out with a number of Policemen, and hooligans trying to resist arrest.

Arrests were made, mainly of the boxers and their aides, and the case went to Bow Street Police Court on 5th April 1882, before the Magistrate, Mr Vaughan. The main issue was whether it was a Sporting Match (legal) or a Prize Fight (illegal)?

Sugar was charged, on remand, with being a principal engaged in a prize-fight on the 27th March at No. 11, St. Andrew’s Hall, Tavistock Place; and nine men, named Aaron Moss, William Scott, John Satchell, John M’Carthy, Thomas Morris, James Lilly, Thomas Davis, George Lewis, and Richard Smith, were charged, on remand, as principals, aiding and abetting. Dennis Harrington (Denny, Sugar’s trainer) was charged, on a warrant, with aiding and abetting in the alleged prize-fight.

The prosecutor, Mr. Poland referred to the case of “the Queen v. Morton and others,” in which a decision was given on April 16, 1878. The learned counsel observed that if persons engaged in sparring there was no offence if it was done in sport, but if there was a fight arranged with the intention of fighting for money, or with a view of knocking each other out, with or without gloves, of course an offence was constituted. He proposed to call evidence in support of the allegation that in the present case a prize-fight had been fought, and after that evidence had been supplemented by other witnesses, he would ask for the committal of the whole of the defendants for trial.

In court the Police claimed that the boxers did not have regular boxing gloves, and Detective Scandrett claimed that Sugar had kicked his opponent when he was down, and that the spectators had hit Sugar with sticks at this point. At this Sugar took great umbridge and interrupted the witness shouting

“Well, I have got three little sons at home, and if they are going to say anything like that I hope they’ll die.”

Mr. Vaughan the magistrate admonished him with:

“Don’t make observations of that sort.”

Sugar continued:

“Oh, I can’t stand it! It would be better to be chucked in the river than listen to such lies.”

The Magistrate gave him his final warning:

“I will have you removed if you continue to behave in that manner.”

The matter was then adjourned so hat character witnesses could be called.

At the second session witnesses for the defence were called, who as was to be expected, all agreed it was not a Prize Fight, that the gloves used were normal boxing gloves, and that they’d seen no cheating, kicking etc in the bout. Most of these witnesses were ordinary working people, some with boxing training as a sport. Amusingly one of them a Cabinet Maker, when asked by one a of the Defence Barrister:

“I do not know if you understand Latin. These people are indicted for a riot. Did you notice anything “in terrorem populi“?

A legal term meaning “to cause fear to the Public”, to which the Cabinetmaker replied:

“I didn’t see him there!”

To much laughter in the court.

The defence also called a number of character witnesses, including a Police man; Detective-Sergeant Thick who said that:

“Goodson had, on one occasion, rendered him great assistance in arresting a man charged with stealing a watch and chain, and who, but for the intervention by him, would have been rescued by the mob.”

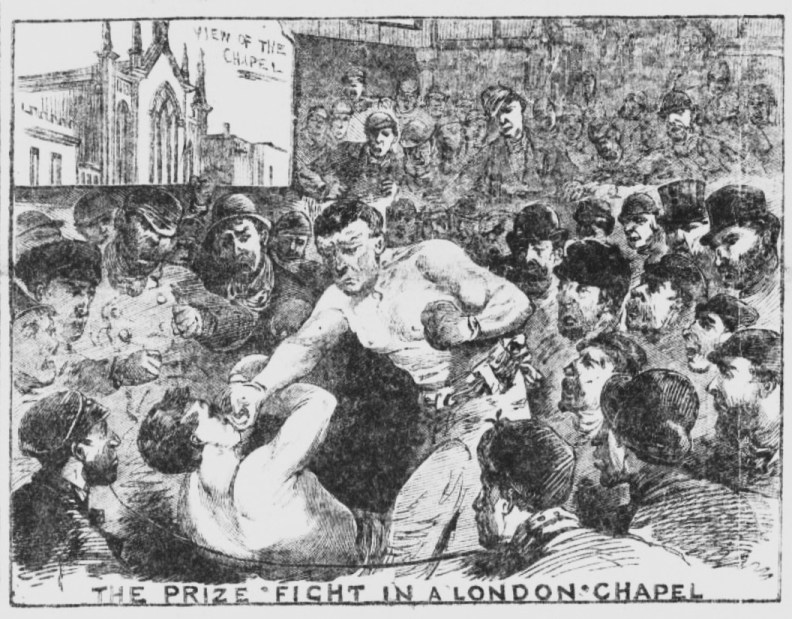

Although not pertinent to the legality of the case, the main outrage, outside of the usual Middle Class fear of Working Class Men, was the fact that the venue had previously been used as a Chapel, although there is no evidence that the either of the fighters, nor many of the others there were particularly aware of the fact, but it became the big part of the headlines in the Newspapers across the country “Fight In a Chapel” bringing up images of Holy relics being vandalised, and worshippers scattered, which was of course nonsense, but a great “Newspaper bait” headline.

The upshot of the trial was a plea bargain, where the boxers agreed to a minor charge of “Affray” effectively fighting in public, in exchange for other charges being dropped, such as “Riot” or more formal charges around Prize Fighting, which were considered a much more serious charges, but hard for the Police to make stick in front of a jury. They walked away with a, by the standards of the day, large fine, and charged to keep the peace. The furore put to bed, a short time later, Sugar and Hicks staged a sparing session for a paying crowd for a single round, and shook hands flamboyantly at the end of it, much to the delight of the audience, in a kind of symbolic “giving two fingers” to the authorities.

Barn Dance: Eltham Kent 1884

Sugar had many more sparring bouts, and more often than not acted as MC for other events notably at the Bluecoat Boy, but the lure of a big payout still exerted its pull on him. In 1884 he was once more arrested for Prize Fighting at a Barn in Eltham Kent, a short train ride from Central London, a nice little day out for the London Cockney Boxing clientele.

Henry Goodson, William England, James Hulls, George Coe, and Thomas Hyams were charged with unlawfully assembling, rioting, assault, and conspiracy in connection with an illegal fight held in a barn at Lime Farm, Eltham, on the evening of 10 January 1884.

Police officers David Smart, Alfred Mooney, Hugo Bell, William Paltridge, George Rosendale, and Thomas Burnett gave evidence that they secretly observed the event through holes and cracks in the barn. Inside, approximately 70–80 men were gathered around a roped ring measuring roughly 16 by 18 feet. A bright gas light illuminated the barn. Goodson and England were said to be stripped to the waist and fighting with bare fists, with no gloves visible.

The officers testified that they saw repeated exchanges of blows. Goodson was struck on the chin and in the chest, and England was hit on the lower part of the neck. Bell testified that England knocked Goodson down with a blow to the left breast. Time was called repeatedly by James Hulls, who was seen standing beside the ring with a watch and a memorandum book, recording the rounds. During breaks, two men entered the ring, wiped the fighters down with loose hay and cloths, and water pails were present nearby. The fight then resumed.

When the doors were broken open, there was a general rush to escape. James Hulls attempted to flee, violently struggled with officers, and discarded papers later identified as sporting documents. George Coe and Thomas Hyams were apprehended near the doorway; Coe claimed he had not been inside the barn, and Hyams pleaded to be released for the sake of his wife.

After the police forced entry, Sugar was arrested inside the ring and taken to the local Police Station where officers observed visible injuries on him, including a bleeding scratch on the top and left side of his head, a fresh black eye (noted to be on his previously blind eye), and a bloodied scratch on his left shoulder. There was no significant blood on either fighter’s face at the time of observation. England was not reported to have visible injuries. The presence of visible injuries were often put forward by the Police as evidence of fighting without gloves, and signs that this was not a sporting “Sparring” match, therefore illegal.

Although a pair of boxing gloves bearing bloodstains was later found on top of a heap of mangold-wurzels some distance from the ring, police witnesses consistently stated that no gloves were worn or seen during the fight itself.

The defendants maintained that the event was a glove sparring match. Goodson, England, and Hulls claimed gloves were used, while Coe denied participation. The charge of riot was withdrawn as the barn was private property, and the case proceeded on unlawful assembly and conspiracy.

The jury found George Coe and Thomas Hyams not guilty, Henry Goodson, William England, and James Hulls were found guilty, fined £10 each, and bound over to keep the peace. This was a large amount of money for a working man, but the Boxers generally had backers and it’s easy to see how they would have assurances for the promoters to take care of any fines should they receive them.

The Professional Boxing Association

In order to avoid further aggravation with the law and to try to organise the Professional Boxing fraternity, at least in London, The Professional Boxing Association was formed around 1885 at various Public House meetings, and the The Bluecoat Boy Public House was prominent, and Sugar and Tom Goodson were active members of the Committee. This tends to negate the idea of the Goodsons as just a pair of ignorant thugs or psychopaths as they are sometimes pictured (especially Sugar). They were uneducated, but not stupid, they knew how to run businesses, and knew they would need to organise if they were to be able to fight against the puritan elements of the Police, Judiciary, and the highbrow press in order to earn a living with their chosen sport. They also knew that a working class Boxer’s career could be short and brutal, so a great part of what the Professional Boxing Association did was to provide for the benefit and families of older boxers and those who died suddenly or fell on hard times. So the body they formed was as much a Guild or Mutual Assurance body as it was a Sports body.

An example of their purpose was shown in a Newspaper Report of 1885 saying the following:

“…notice of motion that at the next general meeting a Defence Fund should be formed to take up cases of boxers who had been, so to speak, “Boycotted” at several places of entertainment. There was no stooping to scientific boxing with the gloves, and the sooner the question was similarly settled the better for all parties.”

The Cockney Boxing entrepreneurs obviously meant business, and were gearing up to do battle for their members outside of the ring.

Boxing contests were billed as “Benefits” for long time fighters, with a proportion on the takings literally being paid to that fighter for their benefit, often if they had fallen on hard times, or were passed their best, or in some other form of perceived need, sometimes just to get punters to turn up and spend as an act of apparent charity, whatever the real reason may have been.

Interestingly, black boxers were treated on an equal footing in the Association with Hezekiah Monroe and Alec Monroe being members and beneficiaries of such Benefit occasions at the Bluecoat Boy, a prime example was that of Charlie Bartlett (sometimes called Bartley) described as “this civil young coloured boxer better known as “The Meat Market Black”. Although this grates on modern ears, it was not meant as derogatory at the time, merely a way of upping the interest in his fights, black people being rare in the UK at the time, and Charlie’s background was one of living in the Smithfield Market area of “The City of London” that had seen a mini-boom in the 1860s with the renovation and updating of The City of London’s main wholesale Meat Market at Smithfield, where workers carried carcasses of pigs and cows for the butchers. This would have made Charlie popular with the hard working hard drinking market porters who would back “their local man” in the ring. Charlie’s benefit turnout wasn’t initially great on the night, as there were a number of other pubs in the area putting on similar events, so Punch and the Goodsons staged a second benefit the following week to make sure he would get a decent payout. The boxing world, to its credit, at a working class level, was surprisingly egalitarian for the time.

Life after Boxing

Once Sugar’s boxing days started to end in the late 1880s, he refused to remain physically inactive, for example in 1886 he helped coach a long distance walking race between two men from Brick Lane. In 1889 he had his last recorded three round Sparring match as a “Grand Wind Up” at a benefit event. In 1890 he took part in a thirty six mile (!) foot race, and in 1895 he ran a race against a publican over 440 yards giving his opponet a 50 yard start, but Sugar lost by 30 yards. In 1897 Sugar received his own benefit night, to raise funds for him.

In 1899 Sugar had applied to become the publican of the Oxford Arms in Spitalfields, but had changed his mind in favour of his eldest son James Henry, and in 1901 Sugar was a Cellarman at the Oxford Arms, and Head of the family, his eldest son James Henry, was listed as the Beerhouse keeper (Publican), also at the address was of course Henry’s wife Ann, James Henry and his wife and daughter, plus Edward and John, Sugars other sons, Edward being a Barman in the pub and John a “Van Guard” i.e. a person who travels in the rear of the Van to stop anyone stealing from it. The family keep the pub through to 1911.

By 1911 Sugar had moved to The Salmon and Ball working as a Carman whilst his younger son Edward Saunders Goodson was running the pub, although it appears that James may actually have been the official licensee, he would transfer the License to Edward Saunders, his brother, in 1926, who relinquished it two years later.

Sugar fought his last professional fight in 1911 at the age of 55! He lost due to a swollen eye. The fight was between two older boxers with a grudge to settle, but when one had to pull out, Sugar stepped up to replace him.

Sugar lived till 1917. Dying at 61 seemed far too young for a man who had been through so much, and done so much in life. He left a wife who he had been married to for forty one years, three sons, and more than twenty Grandchildren, they in turn have left many descendants to this day in and around London ,and further afield. He had a full and successful life and was highly popular both as a boxer and in life generally.

One Reply to “The Real Lives of “A Thousand Blows” Part 3 : Sugar Goodson”