Origins of the Family

In Faversham Kent

The Foreman name is predominantly an eastern England Coastal name. From Northumberland in the North to Kent in the South the name spreads down the English coastline, with the notable almost exception of Essex where the name’s history is sparse. Jamie’s ancestors were no exception to this rule. The name is Old English, and most likely derivation is from “foremost” or “leading” man, exactly as the work position of foreman in the building trade denotes a leader of a team of men, the same was true of the first holders of this name, in this case perhaps a leader of a team of shipwrights or carpenters. The fact that the name distribution corresponds roughly to the areas first settled by the Angles and Jutes, among the sophisticated seagoing communities of the Romano/Belgic British on the east coast of England, may indicate that this was a name applied by the Germanic incomers to leaders of craftsmen from the original inhabitants of the area who were still prized for their abilities in carpentry and metalwork.

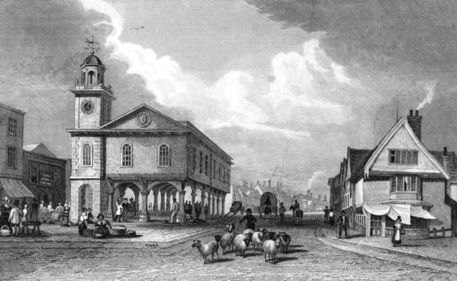

The Creek at Faversham held twelve feet of water at a high tide, so could accommodate most trading vessels of the mediaeval period, and an ancient quay called “The Thorn” had been built to make good use of the deeper parts of the channel near shore. The Isle of Sheppey nearby is derived from Old English “The Isle of Sheep” and the town thrived under the Normans, and reached a Mediaeval peek with the Wool trade that made Britain rich. The Traders of Faversham although always in the shadow of the bigger port of Chatham, none the less, built a steady trade between London and Europe, and the town slowly grew.

The boom in building in London from the 18th century made the need for bricks an urgency, and Faversham was ideally placed to ship the yellow Kentish clay bricks up the Thames, straight into the heart of the capital. Being a busy port the one trade that was guaranteed was that of Boat Building, and from at least the 1700s onwards there was a family in Faversham building the boats of the wool traders, the brick traders and Oyster fishermen. These were the Foremans.

For at least 200 years from the 1600s into the 1800s smuggling was rife along Faversham Creek, even remarked upon by Daniel Defoe, lamenting the growth of the town on the back of it. So throughout most of coastal Kent smuggling was accepted and often supported, larger enterprises being financed from London. Smugglers maintained this position above the law by a mixture of threat, bribery, goodwill, and family connections. An enterprising family of boatbuilders may have avoided a little tax here and there themselves.

Faversham was ideally placed to support the smugglers, it provided a good port away from the Naval base at Sheerness on Sheppey, and the excise cutters at Whistable. Surrounded by mud flats, Salt Marshes, with many inlets and creeks, their navigability known only to local men in small boats, and yet the main Faversham Creek deep enough for a large North Sea trading ship. With the Isle of Sheppey and the swift currents of the Swale providing both cover and means of escape to the smugglers’ fast cutters, and the short passage to France and Flanders reducing the time needed to be at sea, meaning the Faversham Smugglers were not liable to be under the noses of the patrolling revenue cutters for very long.The Gangs, or “Companies” as they liked to style themselves, along the North Kent Coast tended to be smaller than the big organised Gangs of other parts of Kent, Sussex, and Hampshire, therefore attracted less attention from the authorities. For example the smuggler gangs of Deal were so big notorious and well organised that in 1785 1,000 troops were sent in to attack the town and try to capture their boats! The smugglers of Faversham were more low key, although openly brazen none-the-less, as when in 1821 two smugglers from the North Kent Company were captured by the excise men as part of a Naval Blockade, and marched to the gaol in Faversham, only to be released a few days later when the gang attacked the town gaol. A £100 reward (equivalent of about £5,000 today) was posted, but the men were never recaptured. Faversham had the added advantage of the Oyster trade with the Dutch who turned up surprisingly low in the water for boats with empty holds when coming to legally purchase the Faversham Oysters.

Samuel Foreman 1810-1897

and

Ann Transom 1811-1898

The Foreman’s had been documented as shipwrights and carpenters in Faversham from at least the mid 1700s. Their grandfathers may have been among the “…rabble of seamen and others..” who captured James II on 12th december 1688 during his attempt to flee to France at the end of his fairly disastrous reign. So Faversham was not a backwater, it was a place with far reaching connections within the Kingdom and the world beyond.

The friction with France during the 18th century was a boon to the Foremans, they were building ships throughout the period of the wars with France into the Napoleonic Wars and the early 19th century; the family prospered during this century of warfare and smuggling.

Samuel Foreman is the first that we can trace with a direct line to Jamie Foreman. He would have known fairly good living conditions, large houses were built on the back of the legal and illegal trades of the town of Faversham, and there was no reason for any man not to be either gainfully employed, or making money by other means on the waterways of the Town. The attack on the town gaol and the freeing of the two smugglers by the North Kent Company was no doubt witnessed by a ten year old Samuel, whilst the Family took no notice and got on with their work like the rest of the town. Samuel’s father stopping work to use words like Kiplings for the boy’s benefit:

Watch the wall my darling while the Gentlemen go by!

By the 1830s the world was changing, peace at the end of The Napoleonic Wars meant that trade with the continent was ongoing, reducing the relative benefits of smuggling, and many of the gangs had been finally overwhelmed and either hanged or transported to Van Dieman’s land by the authorities. An age of inventiveness, of Businessmen rather than Lords, of steam and engineering was being born in Britain.

Samuel moved up the coast to Dartford in Kent, as there was a demand for skilled men by entrepreneurs like John Hall, originally a Blacksmith and Millwright, who now built steam engines, and was applying his knowledge of iron working to build the engines for new ships. John Hall had purchased the government gunpowder works at Faversham so had a connection with the town that would have made him aware of the best craftsmen there. Samuel would have found good employment in such an environment, and may have met the inventor of the steam engine Richard Trevithick, who had been contracted to come to Dartford by John Hall to build a new type of steam reaction engine for his steamship design. Unfortunately Trevithick would never complete the project as he died suddenly in the Inn in the town, and was buried by Hall’s directors and workmen, the funeral being financed by the sale of his gold watch. Samuel may well have witnessed the great man’s funeral, marking the end of the beginning of the age of Steam.

The coming of the age of the new Queen, Victoria, proved good for Samuel in Dartford, and in 1837 he had saved enough money to return to Faversham to marry a girl from the village of Ospringe, Ann Transom. They returned to Dartford and raised two children in Park Place; Thomas born in 1838 and Sarah born in 1843.In 1849 modernity in the shape of Steam, continued its impact on Samuel with the Steam Railway line coming to dartford. This opened up a less parochial market for Samuel’s talents, and in the same year the family had uprooted and moved to Shoreditch in London, to 3 Appleby Street, off the Kingsland Road. The driver was most certainly work for Samuel, as Appleby Street is within walking distance of the Regent’s Canal and particularly the Kingsland Basin where barges and lighters were moored and repaired. These barges interestingly transported many of the types of commodities that made their way through Faversham to London such as coal from the North East coast, and timber from Scandinavia.

Appleby Street was working class, relatively rough and ready, but nowhere near as bad as many London areas at this time. Arthur Samuel was born within a year or so of their arrival, and the Foremans shared the small two story terraced house with a Bricklayer and his family. Most of their neighbours were London Cockneys, with a small scattering of men from Kent, Surrey, and a few other English Counties.The Family stayed whilst the work lasted into the 1850s, when they would have seen an Italian called Carlo Gatti build ice storage pits by the canal to sell the ice in warmer periods for people to use for simple refrigeration, and also to make ice cream, bringing widespread sales of Italian ice cream to London for the first time, a great treat for the Foreman children.

But the trade on the canal slowly declined, so Samuel and the family once more took the advantage the railway being extended down the Kent coast to Faversham in 1858 and to Faversham Creek in 1860, the foreman’s moved by train back to their roots in Faversham, settling in Abbey Street. Many of the houses in Abbey Street had been privately owned by individual families, but during the 19th century many of these well to do owners had moved out and the houses were now let to tenants, such as the Foreman’s. To Samuel and his family memories of Abbey Street would have been good ones, with well to do families in the street, now it was their turn to live in the same houses, a great contrast to Appleby Street in Shoreditch, but no doubt the children missed the Italian man and his ice cream.

loved reading this about Faversham.

LikeLike