After seeing the Russell Crowe film The Water Diviner, I was impressed by the depth of feeling and unbiased treatment he gave to the subject matter of the Gallipoli Campaign. It reminded me of a true life parallel story of a family whose tree I traced and the stories I turned up, so to mark the 100th anniversary of the Gallipoli Campaign of The First World War, I wrote this blog entry and tend to repost it each Anzac Day. I though I’d share the story with my readers. As poignant as the film.

An Australian Soldier’s English Roots – The Goddings

The Godding Family From England to Australia

The research of the name Godding showed that it is derived from an Old English name “Goding” meaning Goda’s child. The original “Goding” spelling of the name coincides with the early family distribution around the Gloucestershire/Somerset borders, deep in the rural English Countryside.

During the 18th century the age of enclosures came about. In order to meet the higher demand for grain crops the big landowners would seek permissions from Parliament to carry out “Enclosures”, not just the taking of uncultivated waste land, but also land that was communally farmed by the agricultural population, each peasant farmer would have a cow or a pig, or raise vegetable crops on this communal land. The enclosures meant that the Goddings who previously had rights to this land, lost those rights, and with them, the means to make an independent living from small holding, so, having robbed them of their livelihood, the Lord would take them on as paid labourers to work the land they previously had rights over, this, much more than the Industrial Revolution, turned the majority of the population into what they remain today; wage slaves working for another man’s profit. The Lord would also decide what he would pay them. If they didn’t like the wages, they could always decide not to work for the Lord, in which case they would loose their cottage, would have to leave the village to look for work elsewhere as they would not be entitled to poor relief from the Parish, or, of course they could choose to starve to death in a ditch. The landowners had worked out how to control the Goddings and the rest of the local populations with wages and rents rather than through the sword and gibbet. In the words of one MP who railed against the plight of the rural poor;

“The poor in these Parishes may say; Parliament may be tender of property; all I know is I had a cow, and an act of Parliament has taken it from me.”

So this is how William Godding came to be working for wages on local farms dependant on large tenant farmers and the Lord of the Manor, rather than owning a small holding of his own. However, quite suddenly in 1816 when William Godding was still a young man in his twenties, he takes the bold step of moving, not just from his home town of Thornbury, but out of the County of Gloucestershire to Keynsham in Somerset where he meets and marries a local girl named Isabella. Such a move was a major decision for an unskilled Agricultural Labourer, so what could be the cause of it?

Trouble at Thornbury

The enclosure acts had caused resentment between the Lords who took the land and the Peasants who lost it. But the lords had the law on their side and penalties could be harsh for Agricultural Labourers who weren’t prepared to bend the knee to the local Lord.

To take back some of their lost assets, and avoid malnutrition for their families, the local people would poach animals for the pot from the Lords’ lands, which was illegal and violently resented by the Gentry. The penalties were drastic, one member of the Godding family being transported in a prison ship to Australia for such offences in 1810.

At Thornbury in 1815, a man called Thomas Till had been legally killed on the Estate of Lord Ducie by a Spring Gun, a firearm booby trap left in the woods by game keepers to maim and kill the local poachers. Thomas Till had tripped one such weapon and been shot and killed by the device when out looking for a rabbit for the pot. This legally sanctioned killing heightened tensions between the common people and the Gentry in Thornbury which would eventually spill over into confrontation.

On a cold and frosty moonlit night on 18th January 1816 a group of young labourers gathered at a house in Thornbury. They had blacked their faces with soot to aid camouflage and avoid recognition, and deliberately set out on an act of civil disobedience to poach on the lands of Colonel Berkeley at Berkeley Castle. Undoubtedly this was a political move, rather than a pure poaching for the pot exercise, as the leaders of the participants were from middleclass backgrounds, indeed one of the organisers was a lawyer, and guns had been provided, something no peasant would have owned.

However, by the time they reached the Berkeley Estate word had leaked, and a party of ten heavily armed gamekeepers lay in ambush for them. The poachers were challenged by the keepers, and realising that they had been betrayed, decided to make a fight of it. A number of the poachers were soldiers recently returned from defeating Napoleon in France, and men family with cannon fire were not about to quail at the challenge from gamekeepers’ rifles and shot guns. In military fashion hey formed up in a double line, advanced on the keepers and fired a volley; one keeper, William Ingram fell dead, and several others were wounded. After some confused hand to hand fighting and shooting in the darkness the poachers having made their point made good their escape.

Over the following weeks two of the group lost their nerve, gave themselves up and turned King’s Evidence in return for a dropping of charges, the less well-off were apprehended over the following weeks, their fates were mixed; two were hanged for the murder of Ingram, nine were transported for life to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) and another eight (who had the money and connections to facilitate it) fled to America, Ireland, and the Caribbean. No doubt there were many other men involved in the fight that night, but none important enough to warrant a prolonged pursuit. William Godding fled the county as a result the Thornbury Poacher’s Battle.

We find William and Isabella in Keynsham with six of their children, five sons and a daughter. Times were changing, the age of the landed gentry was coming to an end, and the age of the Industrialist was on the rise. This presents opportunities for the Goddings, William gives up work on the land in his fifties to work as a Labourer on the newly arrived Railway, his daughter Elizabeth finds work as a domestic servant at the tender age of fourteen with a Railway Contractor. Times were hard, the children left home and William continues to work as a labourer into his eighties after the death of his wife Isabella.

Vines Godding and the move to Australia

Vines was the son of William and Isabella Godding born in Keynsham Somerset. Vines, was often misspelled as “Fines” due to his West Country accent, and the name would stick. Like his father and brothers he was a Labourer at a time in England when life was very tough for the working man and his family. He had married Sophia Palmer in 1854, and by 1861 they were living in a working class area of Bristol with three children under of five years and under.

With little hope of bettering themselves at home in England, Vines and Sophia were “assisted” in their move to Australia i.e. the costs were covered by a local emigration scheme, as Parishes were eager to rid themselves of the needy poor, and the Colonies were crying out for cheap labour, over and above what would be provided by convicts. So in 1862 they board the good ship the Lady Milton. With Vines and Sophia were their daughters Elizabeth five and Emily three, plus their one year old son Charles. They must have been desperate, because Sophia was also pregnant when they undertook the trip, and gave birth during the voyage to Louisa. After their arrival in Australia times were still terribly hard for the family, disease was rife in the colony among the poor, and both Bessy and Louisa died in 1868, with Elizabeth following in 1888. The rest of the children survived to adulthood. As for the parents, Sophia lived till 1896, and Vines till 1901.

Charles James Godding

One way to survive through hard times was offered by the Army, and with Imperial Wars to fight, the Australians were clamouring to form their own armed forces to support the Empire a full 30 years before World War 1. Vines’ eldest son Charles James, joined the Army as a Gunner in the Artillery on 26th January 1881, he was listed as a Baptist, the first confirmation we have of the Godding family’s religious beliefs. By 3rd March 1885 he was shipped out to the Sudan during the war with the Mahdi, and General Gordan’s siege at Khartoum. The force left Sydney amid much fanfare, generated in part by the holiday declared to allow the public to bid farewell to the troops; the send-off was described as the most festive occasion in the colony’s history.

The NSW contingent arrived and anchored at Sudan’s Red Sea port Suakin on 29th March 1885, and were attached to a brigade composed of Scots, Grenadier, and Coldstream Guards. Shortly after their arrival they marched as part of a large “square” formation – on this occasion made up of 10,000 men – for Tamai, a village some 30 kilometres inland. Although the march was marked only by minor skirmishing, the men saw something of the reality of war as they halted among the dead from a battle which had taken place eleven days before. Further minor skirmishing took place on the next day’s march, but the Australians, now at the rear of the square, sustained only three casualties, none fatal. The infantry reached Tamai, burned whatever huts were standing and returned to Suakin.

After Tamai, the NSW contingent worked on the railway line which was being laid across the desert to the Nile. Far from the excitement they had imagined, the Australians suffered mostly from the enforced idleness of guard duties. When a camel corps was raised, fifty men volunteered immediately. On 6 May they rode on a reconnaissance to Takdul, 28 kilometres from Suakin, again hoping for an encounter with the Sudanese, but the only action that day involved two newspaper correspondents who had accompanied the patrol before leaving the cameleers to file their stories in Suakin. They soon found themselves surrounded by enemy forces, and one was wounded as they fled. The camel corps made only one more sortie – on 15 May, to bury the bodies of men killed in fighting the previous March.

The artillery saw even less action than the infantry. They were posted to Handoub where, having no enemy close enough to engage, they drilled for a month. On 15 May they rejoined the camp at Suakin. Not having participated in any battles, Australian casualties were few: those who died fell to disease rather than enemy action. By May 1885 the British government had decided to abandon the campaign and left only a garrison in Suakin. The Australian contingent sailed for home on 17 May 1885 arriving in Sydney on 19 June. They were expecting to land at Port Jackson and were surprised to disembark at the quarantine station on North Head near Manly as a precaution against disease. One man died of typhoid before the contingent was released.

Five days after their arrival in Sydney the contingent, dressed in their khaki uniforms, marched through the city to a reception at Victoria Barracks where they stood in pouring rain as a number of public figures, including the Governor, the Premier, and Colonel Richardson the commandant of the contingent, gave speeches. It was generally agreed at the time that, no matter how small the military significance of the Australian contribution to the adventure, it was actually this little adventure, rather than the First World War that marked the development of colonial self-confidence and was proof of the enduring link with Britain.

The Grandsons of Vines Godding

The family having seen action in the Sudan, settled down to civilian life, until the next generation were called upon to serve the Empire in The Great War.

Clarence Sydney Godding 1898 – 1917

Clarence was working as a Farm hand on a Dairy Farm, before joining the 19th Battalion of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in 1916 as a Private, and had been living with his parents. On his shipping papers his religion is stated as C of E, but his brother was a Baptist, perhaps he didn’t consider it an important detail. In any case he was shipped out probably initially to Egypt where the Battalion was reorganised and new recruits were trained, before being shipped to France. The first major action for the Battalion was Pozieres, where the German shelling was the most intense ever experienced by the AIF during the war and was accompanied by nearly continuous German counter attacks to recover their vital ground. In this battle 19th Battalion created a record by holding its sector for a period of 12 days. The most notable action that Clarence would have taken part in was the capture and defence of the notorious ‘Maze’ defence system at Flers on 14th November 1916. Clarence and his mates captured and held a salient deep within the German Lines, but their support battalions failed to reach their objectives on the flanks of the 19th, and so the 18 year old Clarence and his unit were cut off deep inside the German lines.

For two days and nights Clarence held his position against counter attacks and intense shelling, almost running out of ammunition Charles and his mates picked up the rifles and ammo of the Germans they had killed and used them, so that their own ammunition could be saved for their Lewis machine guns to stop the German Infantry counter attacks. Of the 451 all ranks who went into the attack, 381 became casualties.

Clarence survived, and his next big battle was at Lagincourt in 1917 where his battalion was involved in the follow-up of German forces after their retreat to the Hindenburg Line. The Germans counter attacked to try to halt their pursuit by the Australians, and Clarence was faced with an attack by a German force that outnumbered them five to one, they made their stand at Lagincourt and managed to defeat the German advance.

On the 3rd of May 1917 Clarence and his friends were thrown into “The Blood Tub” as the second battle of Bullecourt would be called by the Aussies. General Gough had sent his troops to assault the fortress village of Bullecourt using the new wonder ‘tank’ and the Anzacs, it ended in disaster. This was the first battle of Bullecourt, on the 3rd of May Gough launched a second attack on Bullecourt which dominated the British action on the Western Front for two weeks, and was the battle that Clarence fought in. It was the excessive brutality and ferocity of the hand-to-hand fighting that earned Bullecourt the name ‘The Blood Tub’.

At a quarter to four in the morning of 3rd of May 1917 two Australian and one British Brigade went over the top to attack Bullecourt. The Australians penetrated the German line but met determined opposition which stop the force surrounding and cutting off the Germans. It was during this fighting on the first day of the battle in fierce hand to hand combat in the German trenches that Clarence, at the tender age of nineteen was killed. By the end of the battle the village was held by the Allies; the locality turned out to be of little or no strategic importance, and cost the Australians 7,482 in dead and wounded.

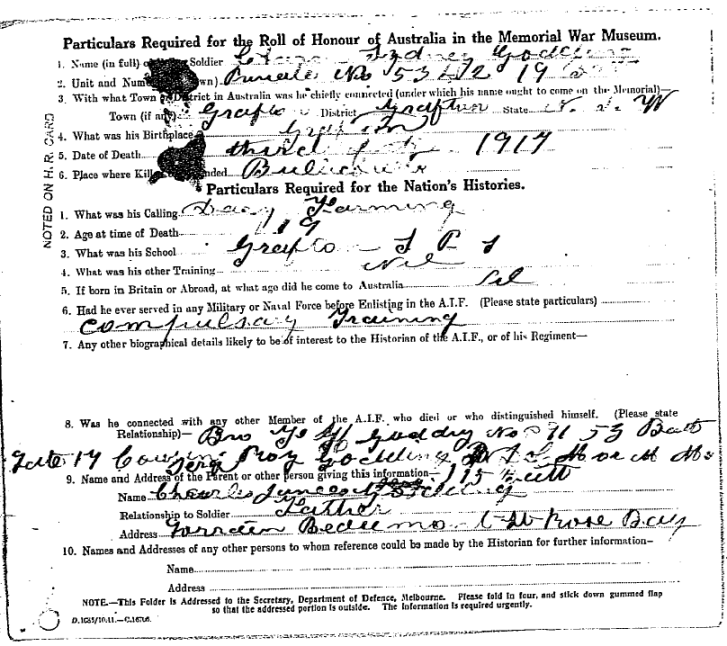

Charles James Godding, Clarence’s Father, made an application to have his son’s name added to the memorial and list on the Roll of Honour. It is a very sad document filled out by a proud but grieving father, the careful but inexpert nature of the writing in a time of grief, contrasts starkly with the bureaucratic and clinical nature of the form; it highlights the gulf in attitude between a statistic and a young man’s life.

Sadly, Clarence’s body was never found, he did not return from the battle, and he was not taken prisoner, so it was beyond doubt that he was killed in action alongside hundreds of others from his Battalion, and by July 1918 his status was changed from missing to killed in action. To the credit of the Australian authorities, they were still investigating right up till October 1919, when they checked to see if he was among Australian prisoners of war released in Germany at the end of the war, but there was no trace of him. All of this was recorded in the archives that we researched.

Although it is not known what happened to his body, he is remembered on the Villers-Bretonneux Memorial in France.

Fines Henry Godding 1896 – 1918

Gallipoli

Fines had worked as a labourer until on 26th February 1915, aged 19, Fines joined the Australian Imperial Force as a Private in the Infantry. He shipped out with the 17th Battalion on the troop ship Themistocles in May 1915. He trained in Egypt from June until mid-August 1915, and on 20 August landed at ANZAC Cove Gallipoli

At Gallipoli Fines fought in the last action of the August Offensive; the attack on Hill 60, it started badly, at the last minute the expected allied artillery bombardment was diverted from Hill 60 to supported the actions at Suvla Bay instead, so the attacking ANZAC and allied troops advanced straight into the ready and waiting Turkish gunfire. Despite this a number of Turkish units abandoned their positions and retreated back to the rear trenches, allowing New Zealand contingents to overrun the forward Turkish positions. This left the New Zealanders exposed ahead of other allied units until the Connaught Rangers, said to be “…mad with the lust for battle” stormed past the Turkish first line of trenches on the New Zealanders’ left flank sending the Turkish defenders running back to rear trenches, the Connaughts were eventually stopped by Turkish machine gun and artillery fire, this pushed them back to the Turkish trenches they had just cleared, where they were eventually relieved by the Gurkhas. On the right flank the Australians and the Hampshire regiment were in support but were hit with accurate artillery fire on the ground they had to cross, made worse by a shell setting the scrub on fire which burned many of the wounded to death.

The next day newly arrived Australian reinforcements, including Fines Godding, inexperienced but fresh and ready for the fight, attacked the Turkish positions with fixed bayonets, and lost over half their entire strength in one dawn attack. A dreadful introduction to modern warfare.

The allies never captured the entire hill, and all positions were constantly counter attacked by the Turks, who maintained their hold on the heights above Suvla Bay. Both sides undermined each other’s positions and exploded mines under them, but it was a stalemate.

Fines’ Battalion was eventually withdrawn from Hill 60 to spend his time in defensive routine in the trenches. Then he found himself as part of the garrison of Quinn’s Post, one of the most contested positions along the entire ANZAC front. It was named after Major Hugh Quinn, the 27-year old commander of C Company, 15th Battalion, Australian Imperial Force. Quinn was killed on 29 May whilst reconnoitring for an attack to recapture trenches seized by the Turks earlier in the day. It was held by Fines’s unit until the evacuation of the Australians from Gallipoli. Fighting was intense, with heavy casualties on both sides, as it was a key position at the end of the Anzac line. It was overlooked by Turkish positions on three sides, and subjected to incessant sniper activity, and to grenade bombardment from Turkish positions only 15 metres away. The Turkish name for the position was Bomba Sirt (bomb ridge). Wire nets were erected in front of the trenches to stop grenades. In his official history, the Australian historian, Charles Bean described the holding of the post as amongst the finest achievements of the Australian force. Fines was eventually evacuated from Gallipoli in December 1915.

France

After further training in Egypt, Fines was sent to France, landing on 22 March 1916. He took part in his first major battle at Pozières between 25 July and 5 August. After a spell in a quieter sector of the front in Belgium, he was sent back into France again in October, where he spent the freezing winter of 1916-17 rotating in and out of trenches in the Somme Valley but was spared from attacking across the quagmire the Somme. It was during this winter that his battalion earned the nickname “the Whale Oil Guards” after their Commanding Officer Lieutenant Colonel Oswald Croshaw, ordered the troops to polish their helmets with the whale oil that had been issued to them as a foot rub to prevent Trench Foot. Trench Foot is caused by prolonged exposure of the feet to damp and cold, it can occur with only twelve hours of exposure, the first signs are numbness in the feet followed by a change in color to red or blue. As the condition worsens, the feet swell, followed by blisters open sores which lead to fungal infections. If not treated it results in gangrene and requires amputation of the foot. Unfortunately for Fines, Croshaw considered a smart turn out on parade more important than his mens’ health. They were Lions led by Donkeys.

In 1917 Fines took part in the pursuit of German forces after their retreat to the Hindenburg Line, and fought in the battle of Lagincourt where a counter stroke by a German force, almost four times as strong, was defeated. Fate then bequeathed that he would fight in the blood bowl at the second battle of Bullecourt (3-4 May), he would have known that Clarence his brother was fighting in the same battle, and no doubt would have had that on his mind during the action. At the end of the Battle, he heard that his brother was missing, and tried desperately to find out what had happened to him sending letters to the authorities to try to find out as the excerpt below shows.

“…his name was in the list of missing last evening, and now it has upset me a great deal. I don’t know how my parents at home will take it when they hear the news, it will be a great blow to them, but still we must of hope for the best. I am giving you his address and if you hear anything different please communicate with me as soon as possible.”

This letter was written from Perham Down, Andover, which was a Convalescent Depot. These were half way houses for casualties returning to the front – men who no longer required hospitalisation but were not yet fit to rejoin their units. Fines had also been wounded at Bullecourt, seriously enough to have been shipped back to England for treatment. At the end of his treatment in July 1917 he wrote another letter to make sure the Department of Wounded and Missing Soldiers would know where to contact him should they get news, as he had been temporarily moved out of the front lines. On the 3rd of September he was still trying to find out the fate of his brother, writing again to the authorities on his return to his battalion. Not knowing his brother’s fate he was shipped back to Belgium, where he fought at the battles of the Menin Road 20th – 22nd September, and Poelcappelle 9th – 10th October. In October his father wrote to the authorities about his missing son Clarence, but also mentioned poignant words about Fines, pleading with the authorities to let his shell shocked son come home, we discovered these heart rending letters in the archives:

The father didn’t get his wish, instead, Fines was shipped out for another winter of trench duty. Fines then took part in the stopping of the German Spring Offensive of 1918. With this last desperate offensive defeated, the Allied armies turned to the offensive. But Fines found himself back in hospital in England. This time he had Trench Fever, a disease spread by body lice in the unhygienic environment of the trenches. Fines was treated in the hospital for just over three weeks, then given two weeks furlough before being shipped back to the front line.

Once back in the lines, Fines received the official letter from the authorities concerning his brother, his worst fears were realised. We can only guess at the pain he carried in his heart as he fought in the battles that pushed the German Army ever closer to defeat: Amiens on 8 August, the legendary attack on Mont St Quentin on 31st August. Then came the last major battle fought by his Battalion which started on 29th September 1918. Two Australian Divisions in co-operation with American forces, attacked the formidable German defences along the St Quentin Canal, and on to the Hindenburg Line.

Unlike his brother Clarence, Fines fate was well documented by his comrades, and we were able to discover in our research many testimonials from them describing what they saw: Private Quantrill went over the top with him at 06.10 on the morning of 30th September 1918 and saw him fall; Sergeant Callaghan saw him lying dead in a trench with machine gun wounds; Private Simmons wrapped his body for burial and noted that he had been hit in the neck and head by machine gun bullets;

Private Green carried his body back for burial after Simmons had wrapped it; and Sergeant Wilkinson oversaw Fines’s burial at Tincourt Cemetery. The actions of his friends who had cared for him and provided some dignity after death must have given some comfort to his grieving parents. His friends refer to him by his nickname as Merry Godding because of his happy disposition. He was 21 years old Turkey and Flanders in some of the bloodiest battles of WW1, but despite all of this he still managed to lift the spirits of his comrades. What greater praise could a man be given?

Private Green carried his body back for burial after Simmons had wrapped it; and Sergeant Wilkinson oversaw Fines’s burial at Tincourt Cemetery. The actions of his friends who had cared for him and provided some dignity after death must have given some comfort to his grieving parents. His friends refer to him by his nickname as Merry Godding because of his happy disposition. He was 21 years old Turkey and Flanders in some of the bloodiest battles of WW1, but despite all of this he still managed to lift the spirits of his comrades. What greater praise could a man be given?

James Keith Godding 1905 – 1943

A sad postscript to this part of the Family’s story is for the youngest brother, James Keith Godding who survived the First World War because he was too young to join up. But when World War Two broke out he followed the path of his elder brothers and father, and volunteered for the Australian Army, like his father joining the artillery, after a brief initial spell in the infantry. Tragically he died of Tuberculosis whilst in the Artillery and still in Australia.

Let’s end on a Happier Note

Roy William Godding

Was born in Newton NSW Australia, the son of Thomas Sydney Godding, and the grandson of Vines Godding. He was a sheep shearer by occupation, and was working in Queensland when he joined the Australian Imperial Force. He was 5ft 8ins tall had dark hair a dark complexion, no doubt tanned from his work shearing in the tropics, and had grey eyes. He had a 34 inch Chest and weighed just over 11 stone, so he was quite heavy for his height, but wasn’t particularly broad in the chest.

He was shipped out as a member of the 15th Infantry Battalion on HMAT Wandilla on 31st January 1916 from Brisbane, and he joined the regiment in Egypt where it had been sent after leaving Gallipoli, so Roy just missed engaging there. Roy proved to be a bit of a tearaway, finding himself in hospital on two separate occasions both for treatment for the results of some leisure activities in Cairo, and he subsequently turns up in Rollestone, Wiltshire, UK in September 1916, where he goes AWL (Absent Without Leave), and is given 16 days confinement to Camp, and lost 16 days pay.

Interestingly the following letter written by the Canon of his parents’ church enquires about Roy as being wounded. His battalion had been in France and had fought in the battle of Pozières in August 1916, so he was wounded and shipped back to England.

By November 1916 he is shipped back to France, and must have started showing his worth as by April 1917 he is promoted to Lance Corporal. This probably happened at the first Battle of Bullecourt, the prelude to the Battle which his cousins fought in. Roy’s battalion suffered heavy losses at Bullecourt when the brigade attacked strong German positions without the promised tank support. During July Roy spent another three weeks in hospital, probably through wounds, It spent much of the remainder of 1917 in Belgium, advancing to the Hindenburg Line, where again he no doubt proved himself being promoted to Corporal and then to Sergeant.

His greatest moment came in September 1917 in the battle of Polygon Wood, in the larger battle of Passchendale. The attack on Polygon Wood was the 5th Division’s first major battle since it was savaged at the disastrous attack at Fromelles in July 1916 (although parts of the Division had been present at Bullecourt in April 1917). It would attack with the Australian 4th Division on its left and five British Divisions also taking part.

The troops advanced in the early hours of September 26, close behind a creeping artillery barrage. The barrage was, in the words of C. E. W. Bean, Australia’s Official War Historian, “the most perfect that ever protected Australian troops”. Under the protection of this barrage, the Australians advanced in several stages. The concrete pillboxes were manned by German machine gun teams who resisted fiercely and almost all had to be captured by acts of individual bravery. The Australians captured the pillboxes in what later became the classic style: a Lewis gun would fire on the pillbox, supported by fire from rifle grenades, while an assault team would manoeuvre around to the back of the pillbox, rather than attacking it head on. The technique worked effectively in most cases, but attacking pillboxes was never an easy task and casualties were seldom small.

It was during this engagement that Roy won The Military Medal. The Military Medal was a military decoration awarded to personnel of the British and Commonwealth Armies, below Officer rank, for bravery in battle on land. It was the other rank’s equivalent to the Military Cross. Recipients of the Military Medal were entitled to use the letters “MM” after their name.

He returned to Australia in 1918, and was demobilised in 1919.